dispatch riders on their motorbikes, circa 1940." width="" />

dispatch riders on their motorbikes, circa 1940." width="" />

Dispatch riders were motorcyclists from World War I and World War II who delivered urgent messages between militaries. Wartime radio transmissions were subject to being unstable and prone to interception at the time, so quick and reliable motorcycle couriers were preferred during these pressing situations.

A job as a soda jerk was ideal for many young people during the 20th century. Youths could often be found handling soda spigots while wearing bow ties and white paper hats as they served up ice cream and soda drinks to order. Competition from fast food restaurants and drive-ins aided in the disappearance of the traditional soda jerk, but today there are many restaurants trying to offer their own spin on the beloved drugstore clerks.

The 1600s weren't known for being an exceptionally clean time in human history. To combat the lack of hygiene, herb strewers were appointed to spread herbs and flowers throughout royal family residences to mask the scent of repulsive odors. Plants like basil, lavender, chamomile, and roses were regularly used by herb strewers.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, some booksellers traveled door to door rather than setting up a brick-and-mortar location. Book peddlers would carry samples of the books and illustrations they offered to promote their products. They were often met with positive feedback, unlike other door-to-door salesmen at the time (of, say, sewing machines and snake oil-like pharmaceuticals). In fact, several states passed laws to prevent soliciting, but book peddlers were often an exception. Today, a few companies still try the door-to-door approach, but concerned residents do not view the cold-calls as positively as in years past.

The Daguerreotype was the first form of the camera available to the public. It was immensely popular throughout the mid-19th century and captured portraits of many celebrities and politicians of the time, like Abraham Lincoln, Walt Whitman, and Frederick Douglass. Daguerreotypists were responsible for capturing photos with their cameras and developing them through a chemical process. Eventually new, cheaper processes were introduced, rendering daguerreotypists obsolete.

during World War I." width="" />

during World War I." width="" />

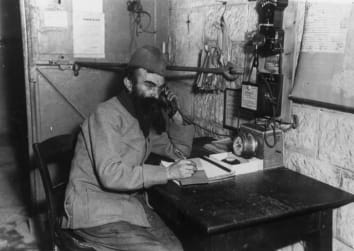

During the telegraph's prime, wartime demand and high salaries made jobs as telegraph operators desirable. Telegraphists were also needed for dispatching between the mainland and those at sea. As forms of communication evolved, the telegraph and Morse code became outdated, but the quick relaying of information brought about by this invention immensely impacted human communication methods as we know them.

You might not find job listings for toad doctors today, but back in the 19th century, the sick in England regularly relied on this folk magic. Patients with scrofula were said to be cured after wearing a toad (either living or dead) in a muslin bag around their neck.

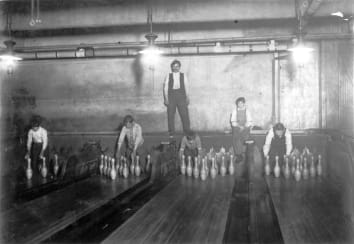

Before automated pin retrieval and set-up machines were invented, someone needed to remove and replace pins at bowling alleys between each turn. These pinsetters (often referred to as pin boys because of the young boys typically employed) would hang out at the end of the lanes and manually reset the pins. As with many rote, manual jobs, when automatic pinsetters began appearing in the first half of the 20th century, the bulk of these paid positions disappeared.

Water carriers (literally, people carrying buckets or bags of water from water sources to residents) had centuries of job security, but as indoor plumbing became popular in the West, this job began disappearing—a pattern that's still spreading to the rest of the world. In 2015, the BBC interviewed a traditional water carrier in India who recalled that even 30 years ago there were hundreds doing that job; he was the last one in his area and singled out the availability of tap water as making the job unviable. And in 2017, the South African network News24 talked to a water carrier from Madagascar who said that in a day she might haul 800 liters of water and earn $1.20.

Cavalrymen are more often thought of as soldiers riding on horseback, but they've also ridden camels and elephants throughout history as well. Fighting by cavalry was a tactical method that gave soldiers enhanced mobility, height, and speed. World War I and World War II were the last major conflicts that relied on cavalrymen. Instead, today's warfare relies on the technology of armored vehicles, aircraft, and modern weapons, though as the recent film 12 Strong dramatized, soldiers and horses do still find themselves working together in many parts of the world.

Radio drama was a leading form of entertainment between the 1920s and the 1950s. Being an audio format forced listeners to rely on music, sound effects, and dialogue to imagine the story being broadcasted. The rise of television brought an end to radio drama and the careers of radio actors, at least in America. In some parts of the world they remain popular, and the rise of podcasts has sparked new interest in audio dramas.

Even if you hate your alarm, waking up to the beeping of a clock sounds appealing compared to paying a knocker-up to rap on your home. During the Industrial Revolution, people were paid to wake clients up for work by knocking on their doors and windows with sticks. Knocker-ups were mostly found in Britain and Ireland, but as alarm clocks became more accessible, the job was eventually put on permanent snooze—though it did hold on in some parts of Britain until the 1970s.

Long before laptops and PCs, people were employed as computers. These jobs were often held by women who worked in teams to figure out lengthy mathematical calculations. Human computers solved problems ranging from astronomy to trigonometry, but as to be expected, these jobs have been replaced by the computers we use today.

Throughout history, the job of a clockkeeper has evolved along with technology. In its early existence, the job involved ringing a large, centralized bell several times a day. Later, when the mechanical clock was invented, winding and upkeep of the city's clocks were necessary tasks to ensure accuracy. Nowadays, clockkeepers are nowhere near as important as they once were, but as The Turret Clock Keeper's Handbook [PDF] explains, "those who care for a turret clock will well know just how highly it is regarded in a local community not only for its grace in adorning a building but also for its timekeeping and its job of sounding the hours—despite all those quartz watches."

Another profession that has been fading out of existence is that of a film projectionist. Using film to project movies in theaters is becoming a rarity now, so there aren't many people who know how to work with film anymore. Having a film projector has become prohibitively expensive, and with the rise of digital projection, the act of spooling canisters of filmstrips is a dying art.

To separate impurities from coal, American coal breakers relied on breaker boys who ranged in age from 8 to 12. This job was often labor-intensive, and the public argued against letting children work in these conditions—but child labor laws were continuously ignored. This continued into the early 1920s until child labor laws began to be more strictly enforced and coal separation technology improved.

Everybody poops—even the former kings of England. These royals just happened to have an advisor, or a Groom of the Stool, to aid them in the process. Though it might sound like a crappy job, the position grew to be powerful and respected within the royal court since kings were known to confide in their Groom of the Stool. The position fell out of service with the rise of Elizabeth I, since the particular title was only extended to male monarchs (Elizabeth I had a comparable Chief Gentlewoman of the Privy Chamber, as well as plenty of ladies-in-waiting and chambermaids at her beck and call). With King James I the position was revived and eventually became known as the Groom of the Stole. And although Queen Victoria's son, as prince, had a Groom of the Stole, the title did not continue into his reign.

The invention of radar technology vastly changed the way that militaries use air defense. Before World War II, the United Kingdom enlisted aircraft listeners. Men in this position would use concrete mirrors to detect the sound of enemy aircraft engines. The acoustic mirrors may have been effective in picking up sound, but they often fell short because enemy airplanes were too close to take preventative action by the time they were heard. Several of these acoustic mirrors have been restored as monuments.

The passenger-operated elevators that we have today are very simple compared to their manual predecessors that needed to have a trained operator. Instead of buttons, older elevators had a lever that would regulate their speed, and the driver would need to be able to land on the right floor. While there are still elevator operators around today, their job is much more focused on security.

Town criers were responsible for publicizing court orders, usually by way of shouting in the street so that everyone in the area was able to hear of the news. In order to gain attention, they'd shout "Oyez"—meaning "hear ye"—and ring a large handheld bell. In England they were known to wear ornate clothing and tricorne hats. Town criers may be disappearing from the payroll, but some can still be found competing with one another or announcing royal births in an unofficial capacity.

Prior to the invention of refrigeration and freezers, people relied on large blocks of ice to keep their food and drinks cool. After letting a foot of ice build up on a body of water, ice cutters were charged with finding, cutting, and handling the slabs for delivery. The job put men at risk in the cold weather and freezing waters; as technology advanced, it was no longer necessary. Today, there are occasional attempts to mine glaciers for "artisanal ice cubes," but the job also clings on in an unlikely place—making ice hotels.

In London during the Middle Ages, link-boys could be found carrying torches along the streets at night. Some were privately employed, while others offered their lighting to pedestrians in exchange for a small fee. As streetlights became more widespread, the illuminating duties of link-boys became a thing of the past.

In the early years of telephones, operators would have to connect callers to each other via a switchboard. This machine had circuits that would light up when a telephone receiver was lifted, and the switchboard operator would then physically connect the lines so people could talk. The profession became outdated once telephone technology advanced to the point that people could dial and receive calls without the middleman. Today the job ostensibly lives on (the Bureau of Labor Statistics estimated 80,000 people were switchboard operators in May 2017), but it's now more a customer service role to make sure callers reach the right department.

Women, called vivandières, served alongside the French army in wars like the French Revolution, the Napoleonic Wars, and the term even popped up during the American Civil War. Vivandières would follow troops, tend to wounds, sew, cook food, and carry canteens for the soldiers—they were essentially mobile medics and maids, but the positions were considered ones of honor and service. The French War Ministry fully disbanded vivandières in the early 1900s before World War I.